Latest AI Tools, Trends & Trusted Reviews!

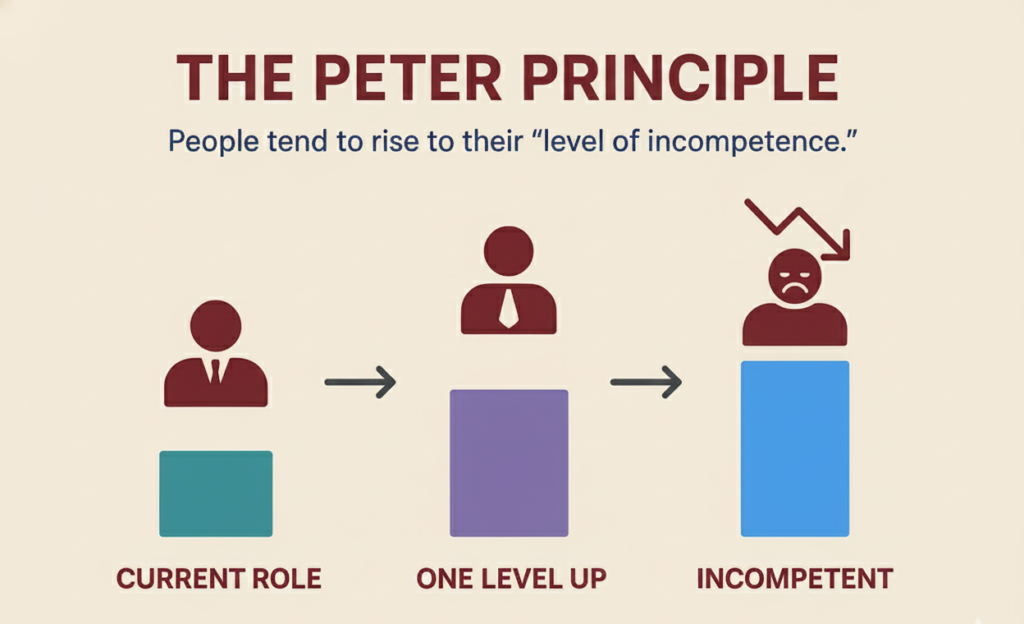

If you’ve ever watched a brilliant individual contributor struggle after a promotion, you’ve already seen the problem we’re tackling. People often search what is the peter principle because it explains a frustrating workplace pattern: teams promote high performers, then performance drops at the new level.

When we reviewed top-ranking pages for this topic, most competitors do three things well: they define the concept, give a few examples, and offer generic tips like “train managers.” Where they fall short is practical diagnosis (how to spot it early), role-specific examples (sales, operations, tech), and modern fixes (skills-based promotion, internal talent marketplaces, and data-driven assessments).

So in this guide, we’ll answer what is the peter principle clearly, then go further: we’ll show how it plays out in real roles (including a territory sales officer), what signals to watch, and how to build promotion systems that don’t punish your best people for being great at their current job.

At FutureTools, we also care about how AI changes work and leadership. That’s why we’ll connect the idea to measurable skills, capability mapping, and smarter talent decisions, not just opinions.

Let’s make it simple. What is the peter principle? It’s the observation that in hierarchical organizations, people tend to get promoted based on success in their current role until they reach a role where they’re no longer competent, often because the new job requires different skills. Gartner describes it as people being promoted until they reach their “level of incompetence.”

This doesn’t mean people are “bad.” It means the promotion system often rewards the wrong indicators. A great doer becomes a manager, but management demands coaching, prioritization, and decision-making under uncertainty. Skills don’t automatically transfer.

You’ll also see this concept defined similarly in major references like Investopedia and Merriam-Webster, which emphasize the “rise to incompetence” pattern in hierarchies.

If you’re still wondering what is the peter principle, try this quick test:

If the answer is yes, the conditions are perfect for the Peter Principle to show up.

A classic place what is the peter principle appears is sales. Imagine a top performer getting promoted to sales manager because they crush their quota. But the management job is different: hiring, pipeline coaching, territory strategy, conflict resolution, forecasting, and running meetings.

In fact, Harvard Business Review summarized research examining promotions in sales across many firms, noting that organizations often promote based on prior role performance rather than managerial potential,then those promoted can underperform as managers.

Now think about a territory sales officer. Their day-to-day success may rely on customer relationships, persistence, negotiation, and deep local market knowledge. A promotion might move them into regional leadership, where they need to develop multiple reps, build consistent processes, and manage long-range planning. Without support, they can feel like they’ve lost the tools that made them successful.

Competitor articles often mention “manager skills,” but we like to get specific. When what is the peter principle hits sales, you typically see:

The fix isn’t to stop promoting great sellers. It’s to separate selling excellence from leadership readiness and to treat management as a distinct profession.

If we keep asking what is the peter principle, the deeper answer becomes: it’s a system problem, not a people problem.

Here are the biggest drivers:

This is where modern talent practices matter. Gartner and other HR sources increasingly push skills-based approaches,mapping roles to capabilities and building learning paths,because it reduces guesswork and future workforce trends shaping leadership and skills.

So when someone asks what is the peter principle, we don’t just define it. We look at what the organization rewards, what it measures, and what it refuses to do (like re-leveling with dignity).

Here’s an analogy our tech-minded readers tend to love.

In energy systems, distributed power management spreads control and optimization across components rather than relying on one overloaded point of decision. When done well, it prevents bottlenecks, overload, and cascading failures.

Now let’s answer the sub-question what is pcs in a relevant way. In electrical and energy contexts, PCS commonly refers to a Power Control System (and sometimes a Power Conversion System, depending on the domain). A power control system monitors and controls power to prevent overloads and keep the system operating safely.

That’s exactly what good promotion systems do. They:

If your org treats promotions like flipping a switch,no calibration, no guardrails,then what is the peter principle becomes your default outcome. But if you build a “PCS-like” talent process (checks, training, gradual ramp), you reduce the risk of failure while keeping growth possible.

![]()

If you’re asking what is the peter principle because you want to avoid it, here’s a playbook we’ve seen work.

1) Create two real career paths (manager + expert)

Pay and prestige must exist for senior IC roles. Otherwise, you push the wrong people into management.

2) Define “next-role” skills like a product spec

List the actual capabilities required (coaching, planning, stakeholder management, hiring). Then evaluate against those,not just last year’s output.

3) Use a probationary “try-on” period

Let candidates lead a project, mentor juniors, or run a small team for 60–90 days with feedback. This reduces surprises.

4) Train new managers immediately (not “someday”)

Competitors often say “provide training,” but timing matters for effective leadership mentoring. Training after the person struggles costs morale and results.

5) Normalize re-leveling without humiliation

Build an off-ramp that protects dignity and compensation where possible. You’ll make smarter decisions faster.

This is how we turn what is the peter principle from a scary “law of nature” into a solvable design flaw.

1) what is the peter principle in simple terms?

It’s the idea that people get promoted based on current success until they reach a job where they don’t perform well, because the new role needs different skills.

2) Is the Peter Principle proven by research?

Research in sales settings suggests promotions often rely on past performance, and some promoted workers underperform in management,consistent with the concept.

3) What’s a real example of the Peter Principle?

A top salesperson becomes a manager but struggles with coaching, hiring, and forecasting, even though they were excellent at selling.

4) How do we stop promoting people to failure?

We evaluate readiness for the next role, offer a trial period, train early, and provide an expert track so promotions aren’t the only reward.

5) Can a territory sales officer be affected by the Peter Principle?

Yes. They may excel at relationship-driven selling but need different strengths for leadership, such as coaching and process design.

6) what is pcs and why does it matter here?

In power systems, PCS can mean a power control system that prevents overload by monitoring and controlling power flow,similar to how good promotion systems prevent “role overload.”

7) Does the Peter Principle mean people shouldn’t get promoted?

No. It means promotions should match the skills needed at the next level, not just reward past results.

8) What’s the fastest warning sign after a promotion?

A sharp drop in team clarity and decision speed, often paired with rising stress, missed priorities, and avoidable conflict.